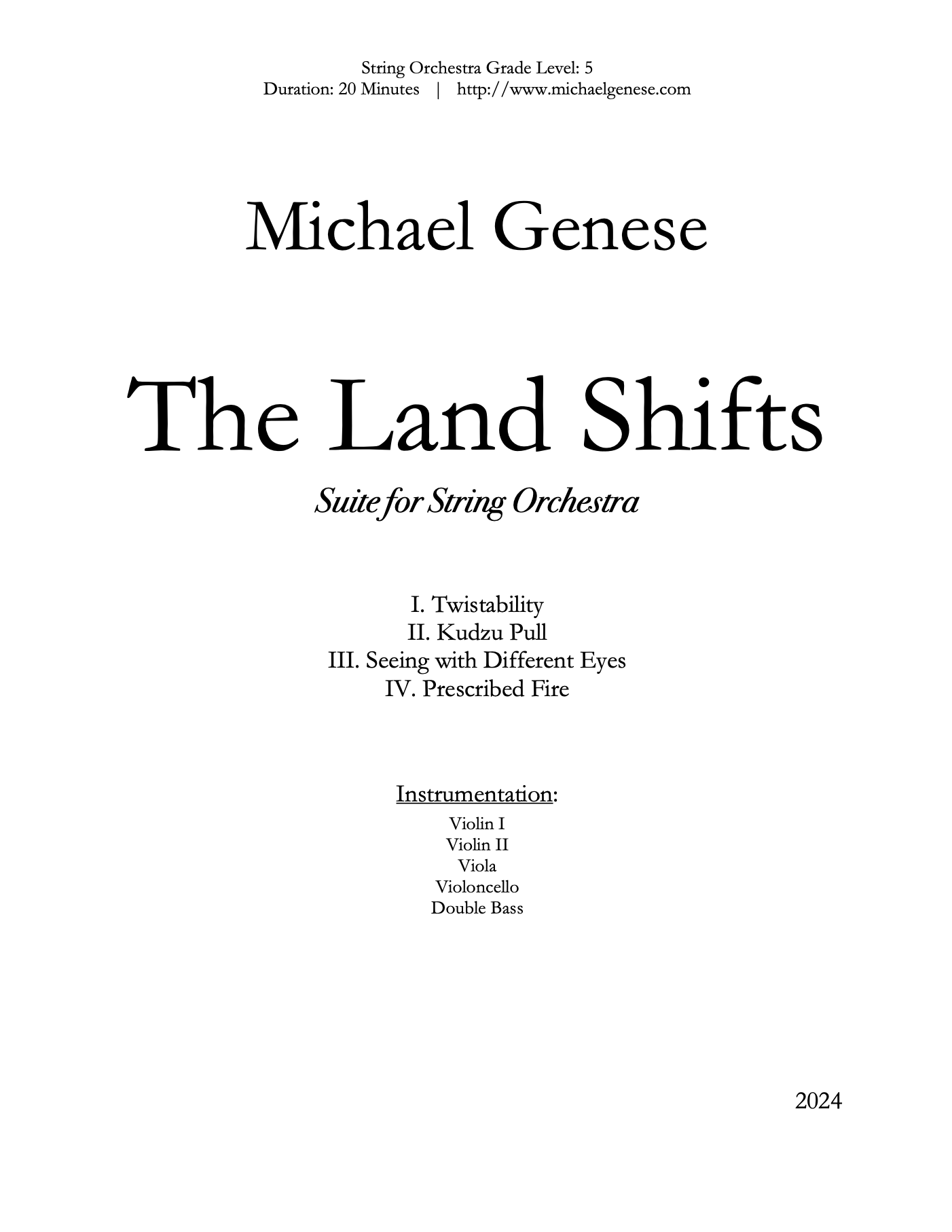

The Land Shifts - Suite for String Orchestra

Duration: 20 Minutes

Difficulty: Grade 5 (grading system details)

Written: 2024

Instrumentation:

-Violin I

-Violin II

-Viola

-Violoncello

-Double Bass

Teaching Materials coming soon!

Program Note:

2024 was the tenth anniversary of my working at the University of Rhode Island Summer Music Academy. As I drove back and forth to campus in July, I noticed a dense, viny ground cover on the sides of the highway that appeared to be charred and burnt at the very top. As I noticed it more and more, I wondered what it was, and worried if our warming and unpredictable climate was to blame. The scope of both the problem and its solution were revealed in due time.

Twisting, pulling, seeing, and burning: The Land Shifts explores these four land-based actions, where either the land or our perspective on it is altered.

Movement I. Twistability lashes out, frustrated and confused about the present. Writhing sforzando’s recede and bubble up again and again, and a quintuplet motif (“Twist-a-bi-li-ty”) twists the six-beat bar into five. The movement's sauntering rhythmic energy asks if we can allow ourselves to twist, to be changed by new knowledge (even if that scares us)? How twistable is the history we’re taught, since other histories are hidden from us? Are we open-hearted enough, to be changed?

Movement II. Kudzu Pull is about “the vine that ate the south.” This plant is invasive to the Americas, which means it takes over entire landscapes, choking out every competitor. In this movement I imagined a group of friends who have gathered together, setting out to pull the vine up bit by bit.

To effectively steward land, we have to learn and know the names of plants that belong in our ecosystems. When kudzu is pulled, what of the existing seed bank underneath? What is the lands history, and will the knowledge of its mistreatment overwhelm us?

This brings us to Movement III. Seeing with different eyes. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer recounts the following:

“One morning in March I stopped by Tom’s place to talk about planting [...] in the spring. I was full of plans for an experimental restoration. [...] We put on our jackets and walked out over the fields. With the right eyes you can almost unsee Route 5, the railroad tracks, and I-90 across the river. You can almost see fields of Iroquois white corn and riverside meadows where women are picking sweetgrass. [...] But the fields where we walk are neither sweetgrass nor corn."

-Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013) pg. 259-260

To know ourselves as part of a present-day landscape, we have to explore this idea of unseeing, and notice how the land shifts. What defines a place like america, if not endless roadways, plastic, and overdevelopment? How can we live in a place that is both so loud and so silent?

Movement IV. Prescribed Fire, the raucous finale, nods to the ancient land management technique of burning portions of land during the cold and wet season, which reduces the amount of flammable ground cover. This prevents larger wildfires during the summer while feeding the existing the seed bank underneath with nutritious ash.

It was only at the end of my week at the string academy that things clicked for me: the dense ground cover near the highway was an invasive species––either Knotweed or Kudzu. Rather than being pulled or burned to make room for native species, someone had sprayed the top with some type of chemical, so it would not grow onto the highway. The climate was not drying the plant out; it was an act of land mismanagement. This perspective shift gutted me, and was a key inspiration for this work, which I hurriedly sketched on a friend's keyboard on the final day of the academy.

Growing up, I always thought global warming was to blame for summer wildfires. In adulthood I learned that Indigenous people routinely introduced fire to the landscape for its benefit, and when millions of them were taken from these lands, the ground-cover was not routinely burned, and the flammable material on the forest floor was not maintained.

Indigenous people make up only 5% of the world's population, but protect approximately 85% of the world's biodiversity through stewardship of Indigenous-managed lands. This bustling musical finale celebrates the joy in taking care of land, urging us to center and learn from its Indigenous stewards. If those who aren’t Indigenous are to be naturalized rather than invasive, sovereignty struggles like Land Back must be at the heart of what we find joyous about being alive, guiding our thinking, actions, and refusals.

Teaching Materials coming soon!